How Cold Does It Have to Be to Cancel School? A Clear, Practical Guide for Parents and Students

Every winter, families across the U.S. and Canada ask the same question: How cold is too cold for school? The answer isn’t simple. School districts do not follow a national rule. They rely on weather data, wind chill charts, transportation conditions, and building readiness reports. This guide explains how districts make these decisions and what temperatures usually trigger closures.

The goal is to help parents understand the signs of a likely “cold day,” and why wind chill—not the number on the thermometer—drives many decisions.

What Temperature Usually Cancels School?

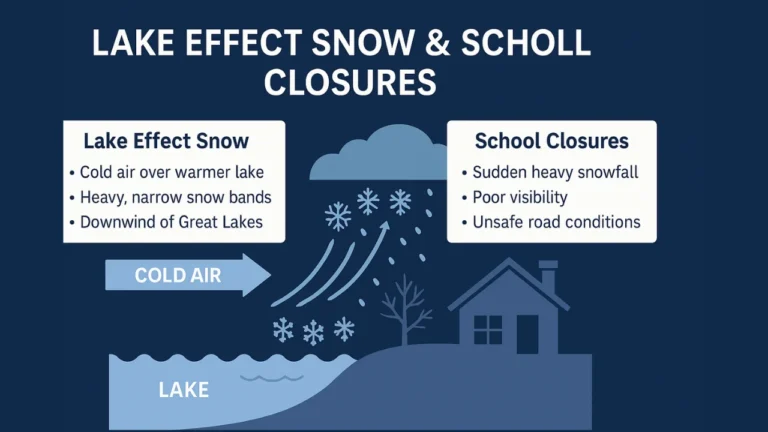

Schools rarely close because of temperature alone. They close when conditions create a credible safety risk during the morning commute. The most consistent indicator is wind chill, not the number on the thermometer.

The National Weather Service wind chill chart shows frostbite can develop within 30 minutes at −20°F wind chill. At −30°F, exposed skin can be damaged even faster. Districts review these thresholds because children stand outdoors at bus stops and walk to school in the early morning. This is why wind chill drives most decisions.

Typical Wind Chill Closure Range (−20°F to −35°F)

Many districts reference the National Weather Service (NWS) Wind Chill Chart.

Here’s the common pattern:

| Wind Chill Level | What Often Happens |

|---|---|

| −10°F to −20°F | School stays open, though families may receive cold-weather advisories. |

| −20°F to −25°F | Some districts consider delays or limited bus service. |

| −25°F to −30°F | Many northern districts close; frostbite risk increases. |

| −30°F to −35°F | High probability of closure; buses and buildings face mechanical strain. |

| Below −35°F | Widespread closures; considered dangerous exposure levels. |

Why Wind Chill Matters More Than Actual Temperature

Wind removes heat from exposed skin. The NWS notes frostbite can develop in 30 minutes at −20°F wind chill, and in 10–15 minutes at −35°F. Because students wait outdoors for buses, wind chill becomes the primary safety metric.

Frostbite Timelines and Exposure Risk at Bus Stops

KiThis is where schools take no chances.

Medical guidance from the CDC notes:

- At −18°F to −25°F wind chill, frostbite can occur in 30 minutes

- At −25°F to −35°F wind chill, frostbite can occur in 10–15 minutes

- Below −35°F, the risk becomes immediate

Children often have exposed faces, wrists, and ankles. Not all families have heavy winter gear. Districts consider these realities when deciding whether the morning commute is safe.

Schools also factor in:

- How long students wait outside

- Whether bus delays are likely

- If younger children can manage extreme cold safely

These practical concerns push districts to act conservatively when temperatures fall sharply.

Four Major Signs Schools Use to Decide Cold-Day Closures

Every district has its own process, but most rely on the same core signals. These indicators come from the National Weather Service (NWS), transportation teams, and building operations staff. When several of these signs appear together, the chances of a closure rise sharply.

Wind Chill Warning or Extreme Cold Alert from NWS

A Wind Chill Warning is one of the strongest predictors of a cold-related school closure.

NWS issues these alerts when wind chill values reach levels that can cause frostbite in 30 minutes or less.

Many districts have publicly stated thresholds linked to NWS alerts:

- Minneapolis Public Schools monitors −35°F wind chill

- Madison and Milwaukee districts use similar limits

- Toronto and Ottawa schools review wind chills below −30°C

These alerts serve as official risk assessments, giving superintendents data-backed justification to close schools.

Districts also track:

- Timing of the coldest hours

- How long the warning will last

- Whether temperatures will recover before dismissal

The morning commute is the most important factor because that’s when children face the cold directly.

Unsafe Roads, Ice, or Bus Start-Up Issues

Cold weather affects transportation long before the first bell rings.

Most public school buses run on diesel. At very low temperatures, diesel can gel, making engines difficult to start. Transportation teams often arrive at bus yards as early as 3:30–4:30 a.m. to test buses in extreme cold. If too many fail, the district cannot operate safely.

At the same time, extreme cold often follows:

- Black ice

- Freezing rain

- Refreezing after snowmelt

- Reduced road traction for early-morning drivers

Counties often post road advisories, and districts coordinate with local highway departments to assess conditions. Even if the temperature alone is not extreme, ice-related hazards can tip the decision toward a closure or delay.rs often conduct 4 AM bus-yard inspections to check whether vehicles start reliably.

Building Heating Problems or Power Instability

Cold snaps push school heating systems to their limit.

Districts track:Older schools are not designed for deep arctic air.

Facility directors often monitor overnight performance of boilers and heating zones. A single malfunctioning unit can drop classroom temperatures below safe levels.

Common issues during extreme cold include:

- Boiler shutdowns

- Frozen pipes or fire-suppression lines

- Uneven heat across large buildings

- Overloaded electrical systems during peak demand

These problems have closed dozens of schools nationwide during past cold waves, including the 2019 polar vortex. Districts know heating failures are unpredictable, and many choose closure when temperatures fall faster than buildings can adapt.

Student Safety Concerns and Clothing Access Equity

Not every family has access to:

- Heavy winter coats

- Waterproof boots

- Gloves

- Thermal layers

Districts acknowledge this openly. During the 2014 cold surge, Chicago Public Schools cited “concerns about adequate winter clothing for all students” as one of the reasons for closing.

Younger children are especially vulnerable. Their bodies lose heat faster, and they cannot regulate temperature as effectively as older students. Schools weigh these risks carefully because one exposure incident is one too many.

Administrators often speak with principals and community liaisons to assess whether students in certain neighborhoods face additional risk. When access gaps appear, closure becomes the safest option.

What Temperature Does It Have to Be to Cancel School?

There is no single national rule for cold-weather closures. Each school district sets its own threshold, shaped by climate, transportation systems, and building conditions. Still, patterns emerge across the U.S. and Canada. Most closures occur when wind chill falls into ranges where frostbite becomes a realistic threat during the morning commute.

Schools rely on NWS wind chill charts, CDC cold-exposure guidance, and their own operational history when deciding. This section breaks down the most common thresholds and the logic behind them.

Common District Thresholds Across the U.S. and Canada

Most cold-day policies focus on wind chill, not air temperature. Here’s what many districts use as a starting point:

| Wind Chill | District Response | Reasoning |

|---|---|---|

| −15°F to −20°F | Increased monitoring | Elevated frostbite risk; buses may slow down |

| −20°F to −30°F | Consider delay or closure | NWS notes frostbite possible within 30 minutes |

| −30°F to −35°F | Frequent closures in northern states | High-risk exposure for walkers and bus riders |

| Below −35°F | Likely closure | Frostbite can occur in 10–15 minutes |

Public examples:

- Minneapolis Public Schools: Reviews closures at −35°F wind chill.

- St. Paul Public Schools: Similar guidelines, shaped by 2014 and 2019 polar vortex events.

- Toronto District School Board: Reviews wind chills approaching −30°C.

- Winnipeg schools: Known for conservative thresholds due to prolonged cold waves.

Why There Is No National Standard Policy

Each district sets rules based on:

- Climate history

- State guidelines

- Transportation fleet age

- Building infrastructure

- Past cold-day incidents

For example, Minneapolis Public Schools often use a −35°F wind chill guideline, while districts in states like Kentucky or Virginia may close closer to −20°F because extreme cold is rare.

How Long Kids Wait Outdoors and Why Exposure Time Matters

Exposure duration is just as important as temperature.

If buses run late—common in extreme cold—the exposure window increases.

Districts compare wait times with NWS frostbite charts.

Special Considerations for Young Children and Health Conditions

Younger children lose heat faster due to higher surface area relative to body mass.

Districts may also consider:

- Asthma risk

- Circulation issues

- Special needs transportation schedules

Key Factors That Drive Cold-Weather School Closures

Cold-weather closures are rarely based on one number. Districts evaluate a combination of safety, logistics, and infrastructure. Their decisions draw on National Weather Service alerts, transportation conditions, facility data, and past cold events. Each factor carries weight because one weak point—whether a frozen bus line or a failing boiler—can put hundreds of students at risk.

Wind Chill & Frostbite Risk (Scientific Basis)

Districts use NWS data and CDC guidance on frostbite to evaluate risk.

Frostbite can occur in:

- 30 minutes at −20°F

- 10–15 minutes at −35°F

- 5–10 minutes below −45°F

Transportation Risks: Bus Yard Checks and Rural Route Hazards

Many closures stem from buses failing to start. Cold weather thickens diesel fuel and reduces battery performance.

Rural districts face the most difficulty due to long, untreated roads.

Building Operations: Boilers, Heating Zones, and Power Load

Large school buildings rely on boilers and multi-zone heating.

When temperatures fall sharply, some zones may fail to reach required indoor temperatures (often 68°F minimum).

Timing of the Cold Snap (Single-Day vs Multi-Day)

A one-day cold blast may not trigger closures.

Sustained cold, however, increases mechanical stress and heating risks.

Cold Day vs Snow Day vs Ice Day — What Actually Closes Schools?

Most families focus on temperature, but schools look at what creates the highest risk. Sometimes extreme cold closes schools with clear roads. Other times a light snowfall won’t stop classes, yet a thin layer of ice will shut down an entire district. Understanding these differences helps you predict closures more accurately.

When Extreme Cold Alone Leads to Cancellation

Cold alone closes schools when it creates conditions that are unsafe for students waiting outdoors, walking, or riding buses. Districts often cite wind chill levels, frostbite timelines, and building performance concerns.

Examples:

- During the 2014 and 2019 polar vortex events, dozens of Midwest districts closed even without snowfall because wind chills fell below −35°F.

- Several Canadian boards, including Toronto and Ottawa, have closed campuses during severe Arctic outbreaks despite dry roads.

Cold-only closures usually occur when:

- Wind chill crosses −25°F to −35°F during the commute

- Buses cannot start reliably

- Heating systems cannot maintain safe indoor temperatures

- Frostbite risk rises beyond acceptable exposure windows

These closures focus on human safety, not surface conditions.

Snowfall Amounts That Impact Opening Decisions

Snow days come from accumulation and visibility, not temperature.

Districts review:

- Overnight snow totals

- How fast the snow is falling

- Road clearing progress

- Visibility during early-morning travel

- Whether plows can make a second pass before buses roll

Heavy snowfall disrupts both urban and rural routes, but the thresholds vary:

- Mountain regions and northern states can operate with several inches

- Southern and coastal states may close with much lower totals due to lack of equipment

A 6-inch snowfall in Minneapolis might be manageable, but the same amount in Kentucky or Virginia can halt transportation systems for days.

Ice and Freezing Rain as Major Closure Triggers

Ice is the most disruptive winter hazard for schools.

Even a thin glaze can shut down an entire district because:

- Buses cannot climb small hills

- Intersections become unpredictable

- School parking lots and walkways turn hazardous

- Power lines and tree limbs snap, causing outages

Many of the most widespread closures in the South and Mid-Atlantic come from ice storms, not snow or cold. The January 2022 freezing rain event in Tennessee and Kentucky is a documented example where districts closed despite moderate temperatures.

Ice also forms rapidly during:

- Overnight refreezing

- Unplowed slush turning solid

- Warm air overrunning cold ground

- Rain falling into subfreezing pavement

Even if temperatures are above zero, ice can be the most dangerous condition students face.

Differences Between Northern and Southern School Districts

Northern districts haGeography plays a major role in closure decisions.

Northern districts (Minnesota, Wisconsin, Michigan, Alberta, Manitoba):

- Have more snowplows

- Maintain larger bus fleets

- Use winter-grade diesel

- Expect repeated cold waves

- Build schools with stronger insulation

Southern districts (Tennessee, Georgia, North Carolina, Oklahoma):

- Have limited snow/ice equipment

- Face more power outages during winter storms

- Experience steep temperature drops that catch infrastructure off guard

- Tend to close earlier because roads become hazardous faster

This is why a temperature or snowfall that feels routine in the Great Lakes region can close schools in the South.

How District Policies Work: Why Two Schools Handle the Same Temperature Differently

Parents often wonder why one district closes during an arctic blast while a neighboring district stays open. The answer is rooted in policy, infrastructure, geography, and operational capacity—not guesswork. Cold-day policies are shaped by long-term climate data, past emergencies, building design, and the realities of student transportation.

Districts track what has worked historically. Many update their policies after major cold events such as the 2014 and 2019 polar vortexes, which pushed wind chills below −40°F across the Midwest and forced widespread closures. These events revealed weaknesses in transportation systems, heating networks, and communication procedures, leading to stricter thresholds in the years that followed.

Northern States with Established Cold-Day Policies

States like Minnesota, Wisconsin, and North Dakota publish formal cold-day guidelines.

Minneapolis and St. Paul are known for using −35°F wind chill as a key threshold.

Regions with Minimal Winter Gear Access or Infrastructure Challenges

Urban districts often factor in clothing access.

Some rural southern districts protect students from cold because buses travel long distances on untreated roads.

Rural vs Urban District Logic

Rural districts may close early due to transportation challenges.

Urban districts may stay open because buses travel shorter distances and roads get treated faster.

Case Studies: Real District Policies and Cold-Day Events

Cold-day decisions evolve after major winter events.

Historical examples show how policies become more structured:

- 2014 Polar Vortex:

Chicago Public Schools, Detroit Public Schools, and dozens of districts across the Midwest closed repeatedly as wind chills hit −40°F to −50°F. Many districts created or revised cold-weather guidelines afterward. - 2019 Arctic Outbreak:

Wind chills again fell below −50°F in parts of Minnesota and Wisconsin. Some districts closed for three consecutive days. Transportation directors later documented large numbers of buses that failed cold-start tests. - 2023 Christmas Cold Wave:

Several districts in Kentucky and West Virginia closed due to a combination of −20°F wind chill, power grid instability, and buildings failing overnight heating checks.

These real events shaped the policies that many districts rely on today. Each cold wave teaches administrators where their systems are strong and where they need reinforcement.

Behind the Decision: How Superintendents Evaluate Extreme Cold

Superintendents do not rely on a single number when deciding whether schools should open. Their process starts hours before sunrise and involves transportation directors, facility managers, local emergency offices, and real-time weather data from the National Weather Service. These decisions carry legal, operational, and safety responsibilities, and the goal is always the same: protect students without disrupting learning unnecessarily.

The following steps reflect how districts across the U.S. and Canada make cold-weather decisions during high-impact events.

Morning Test Drives and Campus Safety Checks

Transportation directors conduct early-morning road checks starting around 4–5 AM.

Reviewing NWS Models, Hourly Forecasts, and Wind Chill Charts

Districts rely heavily on NWS hourly wind chill forecasts, not single temperature readings.

Coordination Between Transportation, Facilities, and District Leadership

Key personnel include:

- Superintendent

- Transportation director

- Facilities manager

- Communications team

Why Neighboring Districts Make Different Choices

Small differences in bus fleets, rural routes, or building heat performance lead to different decisions even on the same day.

Wind Chill, Frostbite, and Hypothermia: The Science Behind “Too Cold for School”

School closure decisions rely heavily on the science of how cold affects the human body. Wind chill, frostbite timelines, and hypothermia risks shape almost every cold-day policy in North America. These are not theoretical numbers—they come from decades of weather research conducted by the National Weather Service (NWS), Environment Canada, and medical guidance from the CDC.

Understanding this science helps parents see why districts act when temperatures fall into dangerous ranges.

How Wind Chill Is Calculated

Wind chill reflects the rate of heat loss from exposed skin.

The NWS formula considers wind speed and air temperature.

Frostbite Risk Levels by Wind Chill

| Wind Chill | Frostbite Time |

|---|---|

| −10°F | ~60 minutes |

| −20°F | ~30 minutes |

| −30°F | 10–15 minutes |

| −40°F | Under 10 minutes |

Hypothermia Risk for Walkers and Bus-Waiting Students

Even mild exposure can trigger hypothermia in young children.

Wet clothing increases risk dramatically.

Science-Based Guidelines Used by Districts

Districts reference:

- CDC cold-weather exposure data

- NWS wind chill charts

- State education safety guidelines

Regional Breakdown: At What Temperature Schools Close in North America

Cold-day decisions vary widely across the U.S. and Canada.

A wind chill that triggers immediate closures in Virginia may be routine in North Dakota. Districts shape policies around their climate, fleet readiness, building age, and historical cold events. The following breakdown shows how different regions respond, based on documented closures and winter-weather policies from 2014 to 2024.

Upper Midwest & Great Plains (MN, WI, ND, SD, MI, IA)

Most closures happen around −30°F to −35°F wind chill.

Northeast & Great Lakes (NY, MA, PA, OH)

Thresholds vary. Many closures start around −20°F to −25°F.

Canada (ON, QC, MB, SK)

Some provinces use −35°C to −40°C wind chill guidelines.

Southern States

Cold days are rare. Closures happen at much warmer temperatures due to limited infrastructure.

How Snow Day Calculators Predict Cold-Weather Closures

Tools that estimate school-closure chances rely on more than temperature. They combine weather data, historical closure patterns, district behavior, and timing to give parents a realistic probability. These systems do not replace official announcements, but they help families understand the risk before districts publish decisions.

Snow Day Calculators use a layered approach similar to how transportation directors, facilities teams, and superintendents evaluate conditions. The tool looks at what has actually caused closures in the past—not just what the forecast says.

Real-Time Temperature, Wind Chill, and Forecast Inputs

Calculators pull data from legitimate weather APIs and NWS forecasts.

Historical District Behavior Patterns

Prediction engines study past closures under similar conditions.

Probability Score Meaning

A 60% chance means conditions meet most—but not all—closure signals.

Why Prediction Tools Help Families Plan

Parents can plan childcare and transportation earlier.

Parent and Student Safety Guidelines for Extreme Cold

Dress Children in Multiple Insulating Layers

Include:

- Thermal base layer

- Insulated coat

- Windproof gloves

- Hat and scarf

Safety Tips for Walkers and Teen Drivers

Cold affects tire traction and reaction time.

Encourage teens to warm vehicles fully before driving.

Monitoring Alerts

Parents should check:

- NWS alerts

- School district email/SMS

- Local news outlets

- District social media

Preparing Backup Plans

If possible, arrange:

- Neighbor check-ins

- Flexible work hours

- Remote learning setups

FAQ: Common Questions About Cold-Weather School Closures

Final Takeaway: Understanding When It’s Truly Too Cold for School

- Most closures occur between −25°F and −35°F wind chill.

- Exposure time and wind speed matter more than the thermometer.

- Buses, buildings, and safety infrastructure heavily influence decisions.

- Tools like Snow Day Calculator help families prepare early.

Extreme cold affects each community differently. Knowing the signs and understanding district logic makes winter planning easier for every family.